Glossary

Logout

©Copyright Arcturus 2022, All Rights Reserved.

7

Terms & Conditions

|

|

|

|

Security & Privacy

Contact

PRODUCT MANAGEMENT CORE PRINCIPLES

|Product Management - In Perspective

The term 'Product Manager' was introduced to business in the 1960's and the role has grown in its popularity ever since, but despite this longevity and continued popularity, it does suffer from a somewhat confused 'terms of reference', ...there is embedded confusion as what the role entails. So it's not surprising to see find 'Product Managers' and associated disciplines, operating in a muddled ad-hoc way deep within inefficient business frameworks. This situation has been further compounded in recent times as what can only be described as a by a myriad of 'product management' interpretations from various training organisations, together with a seemingly endless procession of individual PM voices within management forums etc., ...all with their own convoluted interpretations of what Product Management 'is and, is not'.

Perhaps the main reason behind the number of interpretations of what Product Management is (or is not), stems from the fact that it fundamentally means different things to different companies and is highly dependent on how the actual business is set up in the first place and it's evolving culture within. For some companies, they are completely happy with their own Product Manager's operating like 'fix it fire-fighters' unblocking problems here there and everywhere whilst supporting Development and Sales, whilst other companies expect their Product Managers to perform strategic miracles by transforming the company fortunes and all this without any clear direction or perhaps more importantly without any real authority - surprisingly it simply does not work. There is however a solution...

The PMM framework (developed by IPM in 2008) on the other hand represents a fresh perspective and understanding of how this important discipline can be adopted in virtually any business environment. To further confidence, the original PMM architecture was developed from 1st principles and cross mapped over 14,000 management interdependencies, it was validated by academia and proven in practice.

Needless to say, the management principles embedded within the PMM framework are both generic and eminently scale-able, but they should not be seen as quick fix or indeed a collective of 'magic beans' and a panacea of all ills. That said, this is an extremely powerful framework once correctly deployed, the results are simply outstanding.

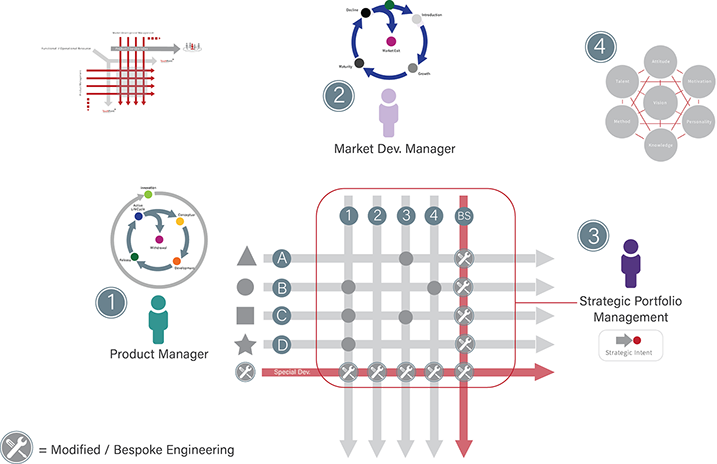

Product Management as described within this site comprises of three primary disciplines / activities (Programme Management, Market Development and Strategic Portfolio Management). To deliver the desired outcome, each individual disciple must work in complete harmony with one another and with one purpose, to deliver 'Strategic Intent' efficiently and effectively - but it must be right for your business - and as with other processes and activities, it must deliver measurable value.

Deploying the PMM framework principles in totality will require a competitive organisation with every 'Functional department' (directs) buying into the core principles thereof - however, this is an excellent opportunity to spell out crystal clear roles, responsibilities and expectations across the organisation.

In practice the Product Manager / Market Development Manager, operating within the PMM framework will instantly become more visible with a clear sense of purpose.

Traditionally, the Product Management activity in general can be described as a discipline within the Functional organisation and therefore thought of as an 'indirect', in other words an overhead to organisation as a whole. However, some organisations have linked Product Management with a 'Functional' department, but this approach is seen as a major compromise. Conversely operating within the PMM framework instantly brings the Product Management discipline into focus, whereby it immediately becomes central and in effect a Customer of the 'Functional' organisation. At a virtual level the Product Management activity can loosely be thought of as the contracts giver to the organisation, whereby the Product Manager, for example, sits in the centre of a 'supply centre', calling upon expertise and resource as and when required by the programme. To this end the Product Manager can effectively manage the tactical arms of the product marketing strategy with military precision, which traditionally has never been the case .

In conclusion, the role of the Product Manager becomes crystal clear - He / She 'owns' the Product (across 6 phases) , writes the Strategy to deliver Strategic Intent and has direct access to resources (multi-disciplinary team) that enable the programme to happen across the product life-cycle. Finally of course... Team Visibility, Responsibility and Accountability, across the entire Product Life-Cycle all come as standard.

|Best Practice Product Management - Primary Elements

A Valid Path

The size, type, maturity and culture of a business plays a major part as to how its own structure evolves over time. When we observe this rationale across wide sections of industry, it has duly led to many interpretations and associated terms of reference for the Product Management discipline. We respectfully understand that your company is unique and special with its' own idiosyncrasies, so whatever your structural / process starting point is, we offer a valid path and embrace 'best practice' and continuous improvement together. ...Lean, efficient, effective and simply right for your organisation.

After many years of practical experience in Product Management, the critical success factors are clear...

Management Disciplines Performing as One

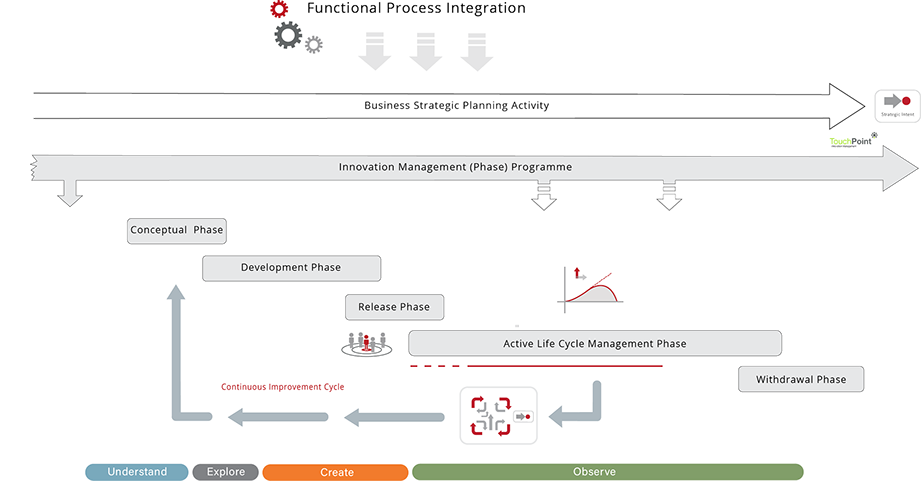

Managing products across their entire life-cycles to deliver on strategic intent, sounds easy, however it remains a considerable challenge to many businesses. All too often the Product Management discipline is simply left to chance and / or mismanaged. The danger of operating in this ad-hoc way of course is that it can lead to a range of undesirable consequences.

Product Management is a key business discipline with numerous time related TouchPoints to be owned and managed. With significant interactions to be pro-actively considered, the result is a complex array of potential outcomes and often requires a triad of management disciplines all performing as one in order to succeed. The 'PMM' process offers a valid path through these complexities, adhering to modern 'Lean' principles throughout, offering the most efficient and effective way to cascade your 'strategic intent' - following method, results in repeatable qualities and outcomes.

You can therefore be assured that the Product Management Methodology (PMM) has the flexibility for your organisation, has been extremely well thought through and includes a complement of modern management methods and processes that align perfectly to best practice interlocks.

Programme Management - Market Development - Strategic Portfolio Management

Product Management can be defined as three primary disciplines / activities (Programme Management, Market Development and Strategic Portfolio Management). To deliver a desired outcome, each individual disciple must work in complete harmony with one another and with one purpose, to deliver 'Strategic Intent' efficiently and effectively - in other words it must be right for your business - and as with other processes and activities, it must deliver measurable value.

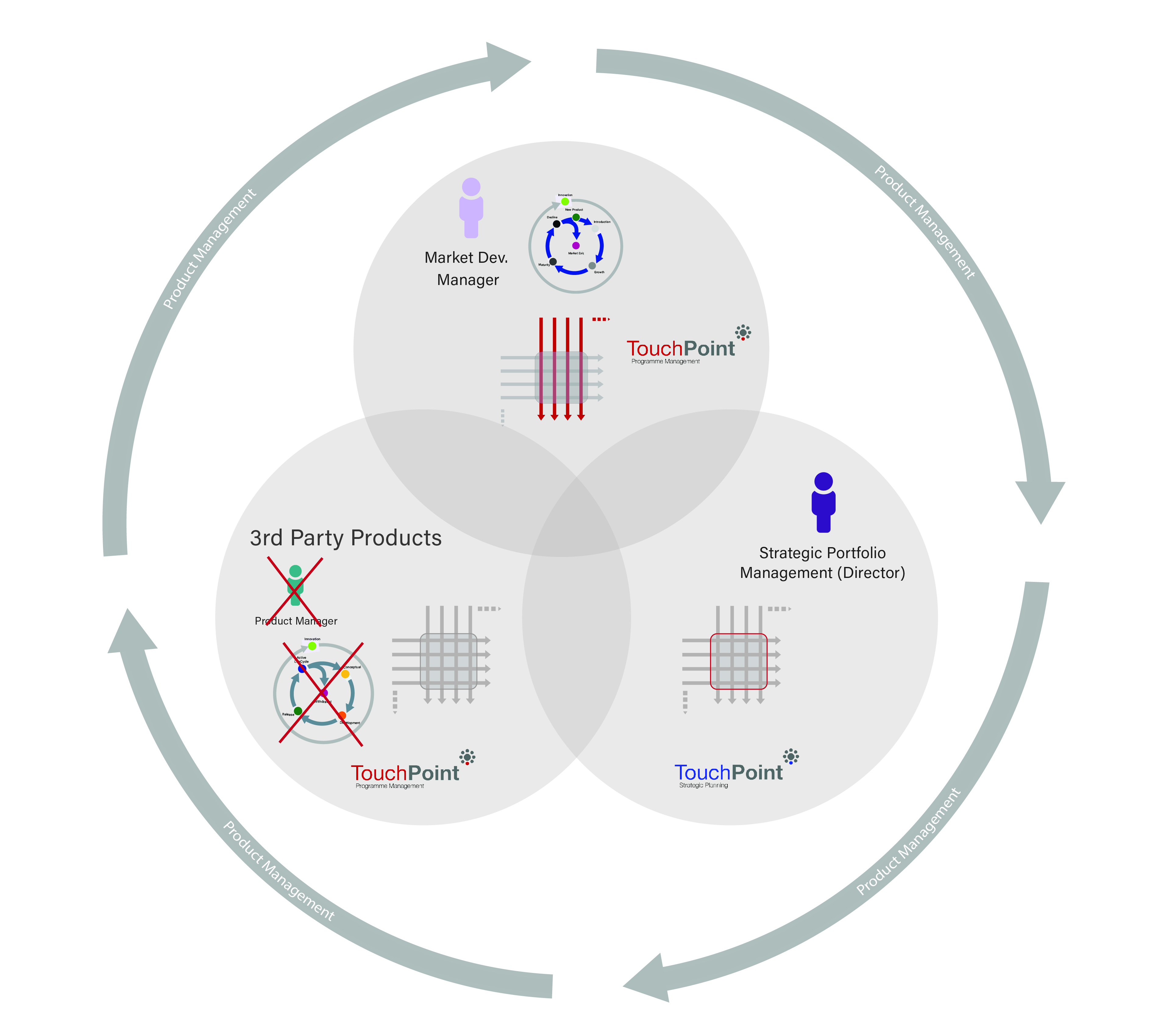

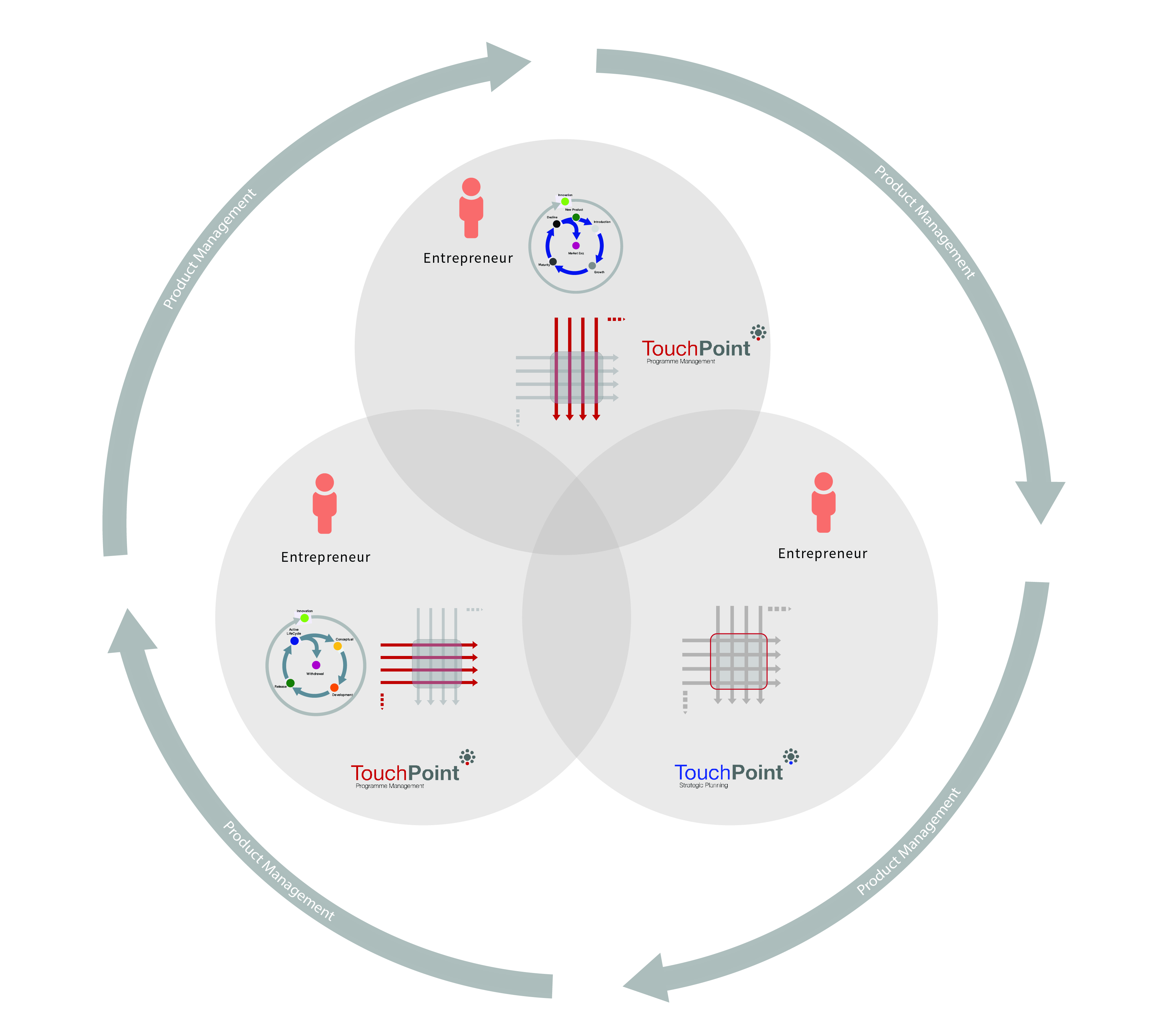

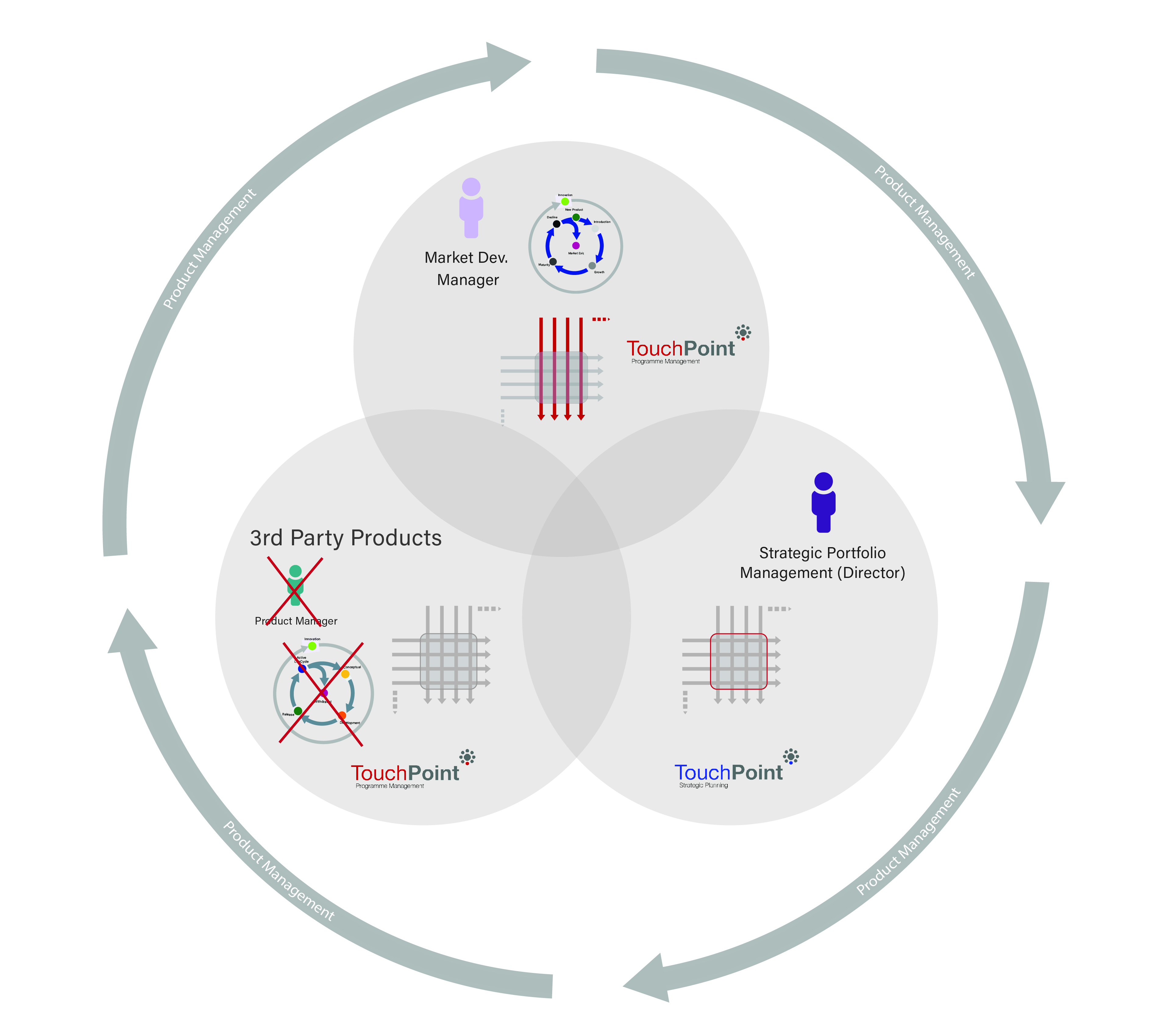

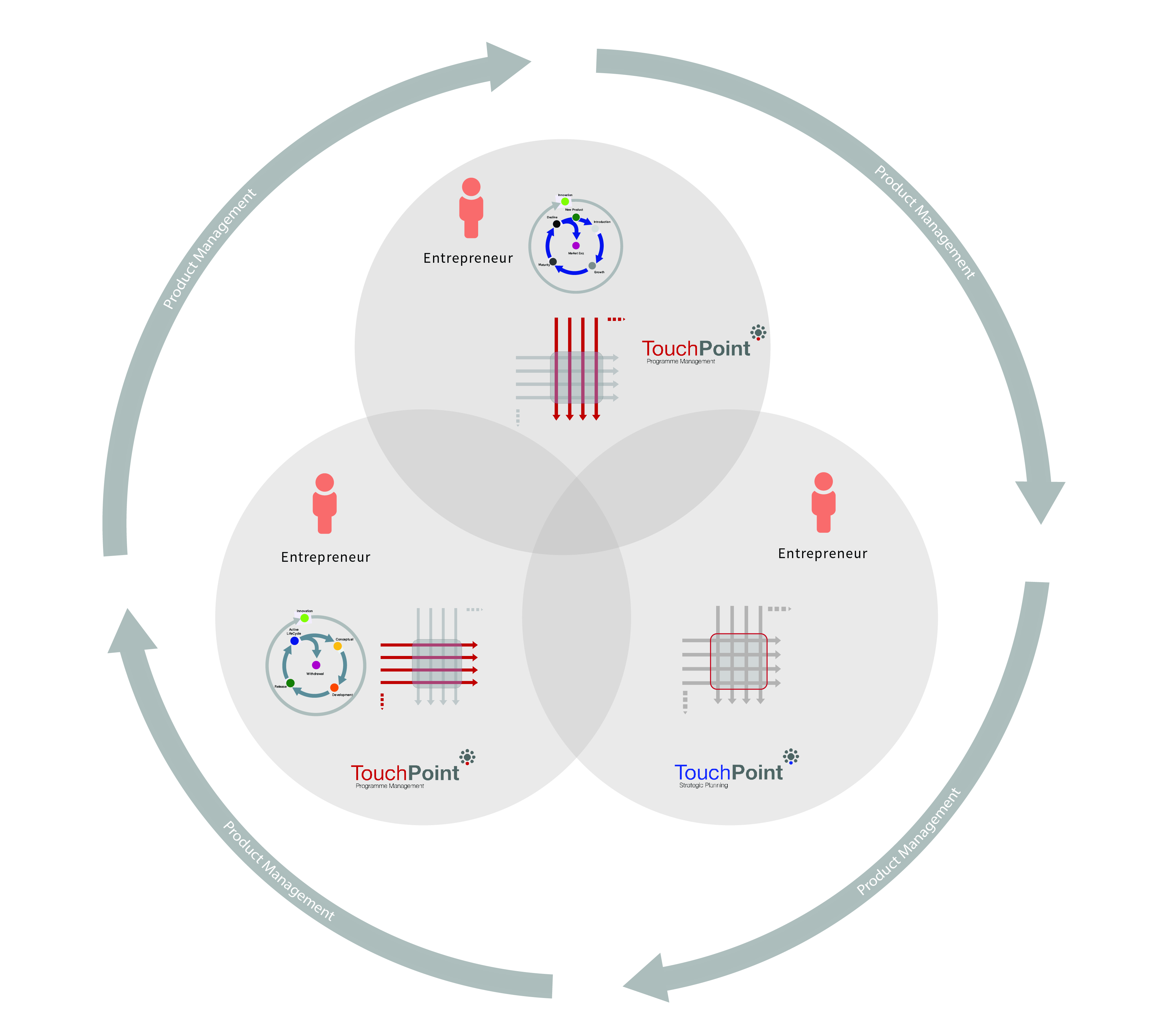

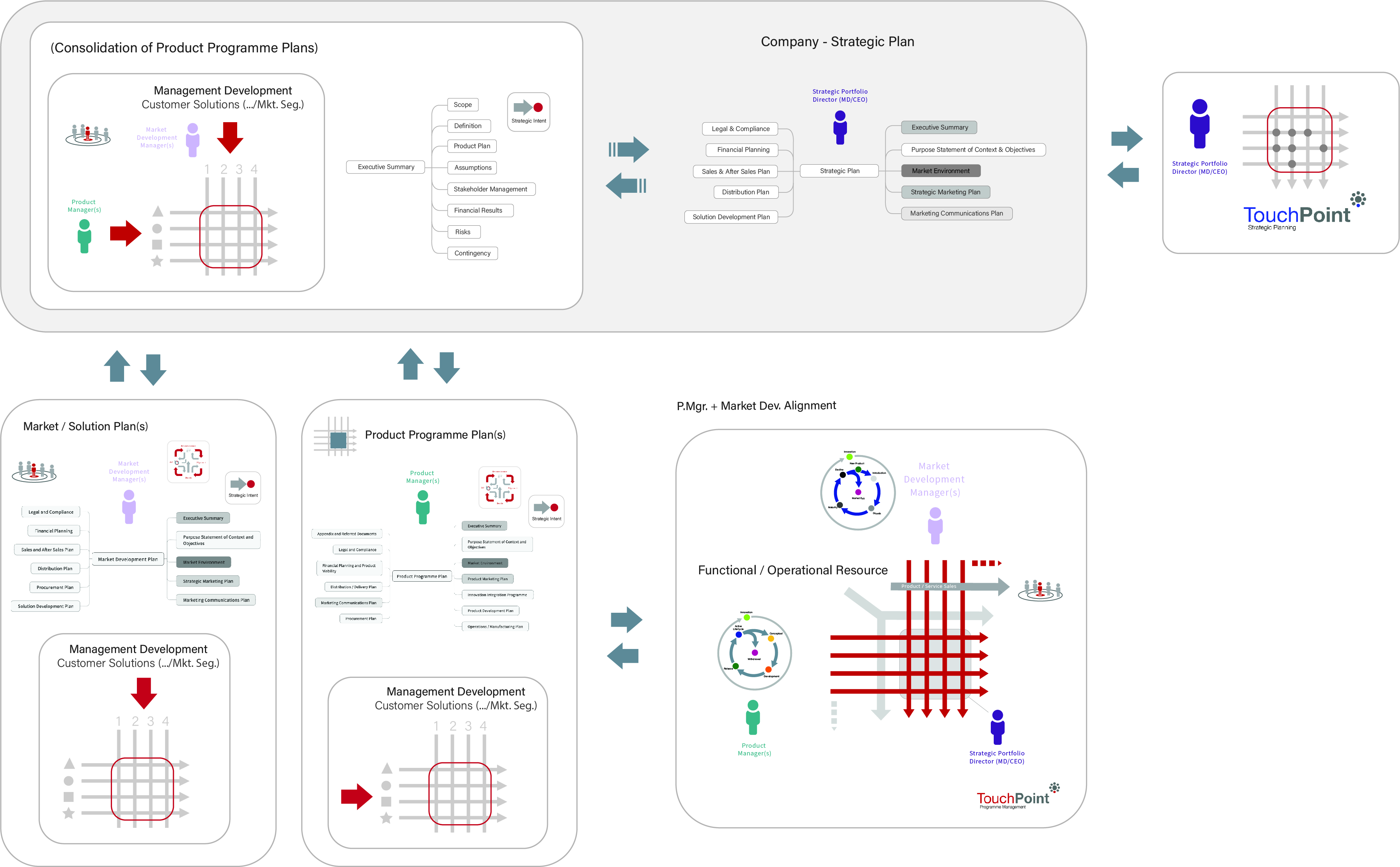

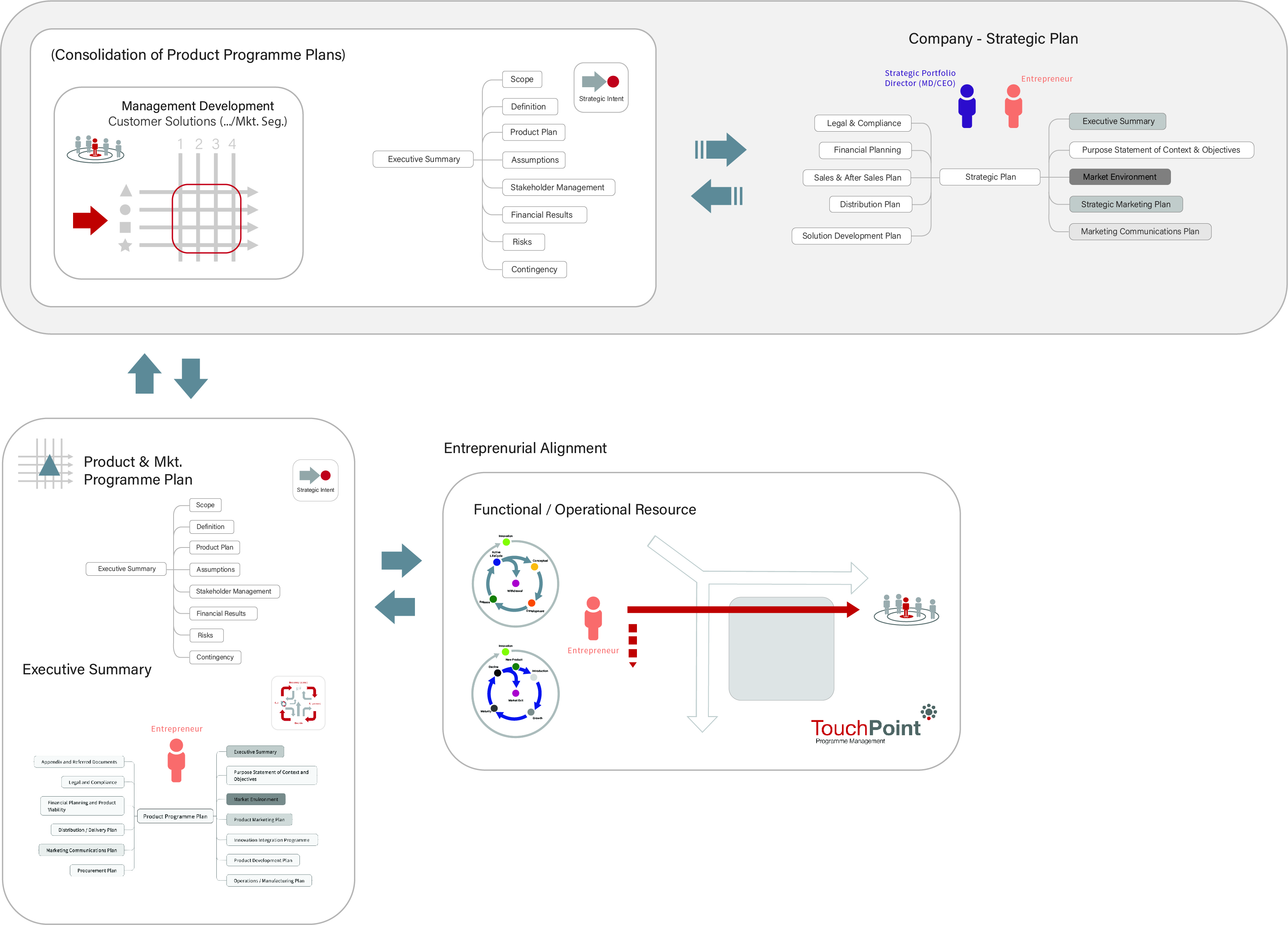

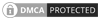

The diagrams below (1 -4) detail the primary alignments associated with Product Management - fundamentally the framework remains (...this is always fixed and does not change) but the core responsibilities change according to business needs and those responsible for the Product Management activity. As such the Product Manager (in title) does not necessarily own or is responsible for the entire Product Management activity. There are a number of reasons for this, not least is, by the time the portfolio Vs the target market reaches a certain size, logistically it becomes to much work and just too complex for one person to handle. The 'Product Manager' is however, as a minimum, responsible for the 'Programme Management' activity - in other words delivering required Products to the matrix but of course there can be more than one Product Manager (in-fact this can be as many as is required).

The following defined variations are 'primary' variants of Product Management activities (alignments) :

1. Product Manager (Programme Management) + Market Development Alignment

2. Market Development Alignment

3. Product Manager Alignment

4. Entrepreneurial (Start-up) Alignment

1

2

3

4

|Product Management - Personified

Framework benefits...

- A continuous lean planning environment that is robust and encourages strong functional ownership throughout the entire Product Management activity.

- Framework promotes professional and cohesive management of products / services throughout the business unit.

- Strategic Intent is delivered with confidence and transparency, risk assessed with nothing left to chance.

- Management traceability of strategic actions across all functional areas- leading to delivery, ownership and accountability.

- Holistic management 'work flow' / 'framework' that pro-actively and efficiently guides the multidisciplinary team from 'Product Innovation' through 'Active LifeCycle' to 'Product Withdrawal' with repeatable precision.

- Integrated business models promotes integrity, clarity and common reporting.

- Fully embraces the principles of lean and continuous Improvement.

- Promotes a strong multi-disciplinary approach to Product Management Control and management of all aspects of the Product Management discipline.

- Highly effective multi-disciplinary team management.

- Market segment alignment.

- Complete alignment with Strategic Intent.

- Strategic alignment to Product Management.

- Market driven 'solutions' not products.

- Clear and effective solution price strategy / deployment.

- Pro-active market reconnaissance direct to product strategy.

- Integrated business models promotes integrity, clarity and common reporting.

- Fully embraces the principles of lean and continuous improvement.

- Promotes a strong multi-disciplinary approach to Product Management control and management of all aspects of the market development discipline.

|Product Management Contextual Alignment

‘Click for Info.’

PMM 'frameworks' have been meticulously designed with an open architectural footprint. This fundamentally enables you manage your Products / Services across individual 'life-cycles' and are structurally generic and robust for use in 'any' business. Obviously there is no such thing as a 'generic business', they come in all shapes and sizes with their own unique quirks and idiosyncrasies. As such, this must be to be taken into account when deploying any management process(es) - it has to be right for the organisation - a management process that is an incorrect fit (a square peg in a round hole) or goes against the culture will ultimately be badly received and soon fall into disrepute. Senior management must therefore genuinely believe in the system / process with a passion and results will undoubtedly flow thereafter.

Traditionally 'Product Management' and other related disciplines, do suffer from a level of confusion as to what the role entails. This is because, as a discipline it is multidimensional and complex with many touch-points and various levels of understanding. This is compounded by the fact the discipline means different things to different Companies. Needless to say, results from a well oiled PM framework are compelling and directly linked to business success. The following generic frameworks will help define a 'valid path' for your own company to follow, in part or full depending upon the need and application.

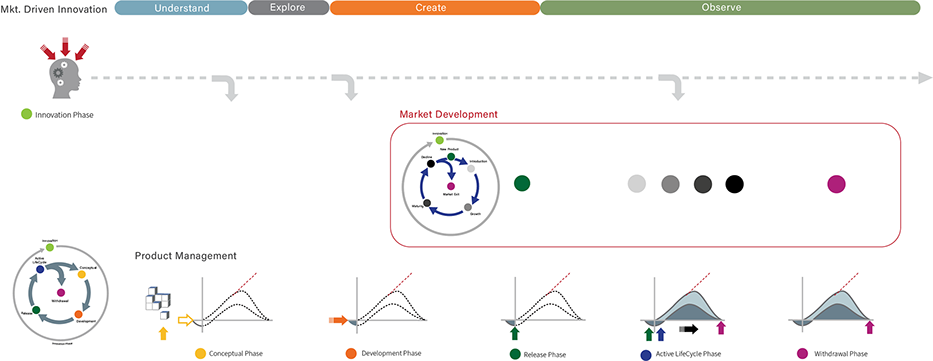

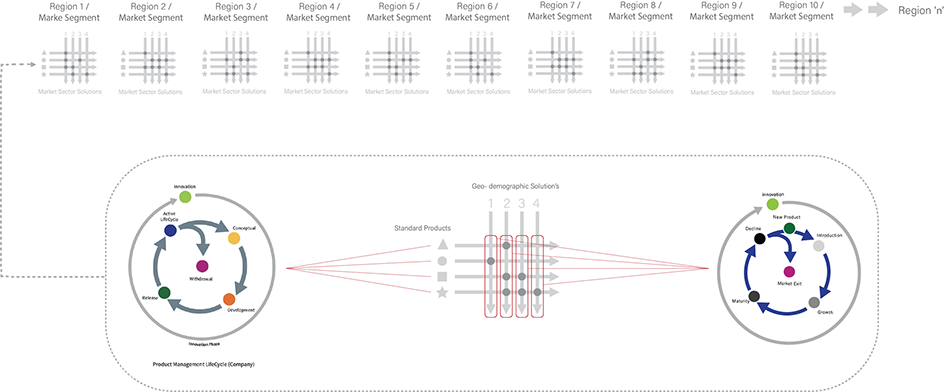

Product Management activities lie at the heart of the (Product) Lifecycle process. As the name suggests a ‘LifeCycle’ is a time related series of events managed in accordance with the requirements of an actioned strategy. Timing also plays a big part in this rationale. The ‘ethos’ of managing the Product LifeCycle is well understood (…in theory) however in practice it becomes somewhat nebulous as there are many variables to be taken into account which are not entirely under our immediate control.

There are effectively two LifeCycles that must be managed. The first of which is the Product Management LifeCycle which is an internal management activity and comprises of six phases:

|Product LifeCycle Management - Programme Management

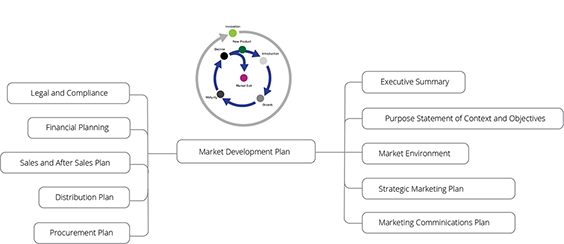

|Product Marketing LifeCycle - Market Development

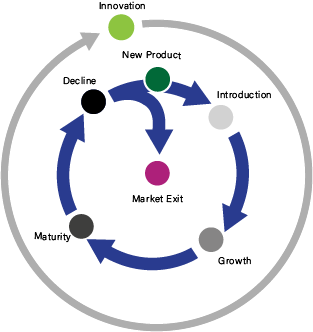

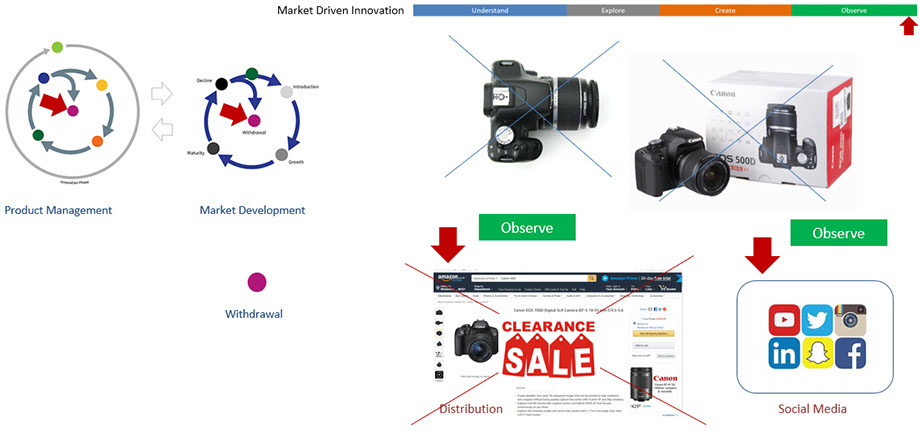

The second LifeCycle, which is interrelated with the first, is a Product LifeCycle from a market perspective. There are five specific phases to this LifeCycle; Introduction, Growth, Maturity and Decline. Each of the phases mentioned are directly related to a time frame which, in turn, is linked to many variables (internal and external).

A product LifeCycle is fundamentally the 'cause & effect' of Strategy, as such, it requires constant observation and adjustment to ensure viability and commercial results tracks with expectations. It should be noted however, that if a product is released and left to its own devices (not managed as such), it will still have a life cycle - but it equally it may never reach your commercial expectations.

|Product (Generic) LifeCycle Example...

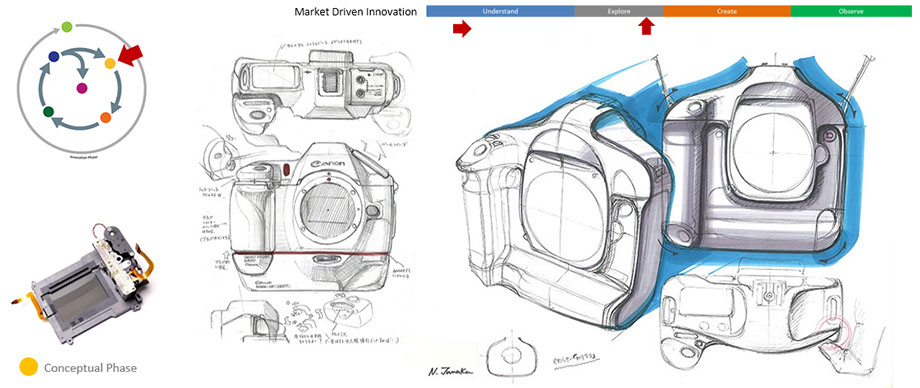

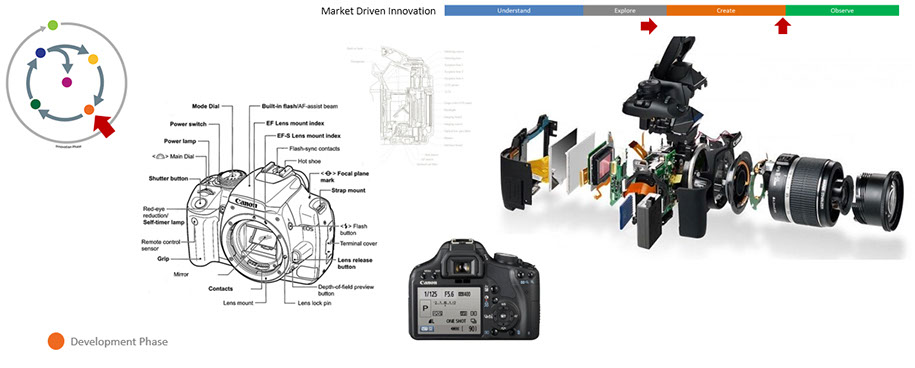

This diagram was produced by IPM for 'example purposes' only - Design ownership and Image copyrights acknowledged.

This diagram was produced by IPM for 'example purposes' only - Design ownership and Image copyrights acknowledged.

This diagram was produced by IPM for 'example purposes' only - Design ownership and Image copyrights acknowledged.

This diagram was produced by IPM for 'example purposes' only - Design ownership and Image copyrights acknowledged.

This diagram was produced by IPM for 'example purposes' only - Design ownership and Image copyrights acknowledged.

|Portfolio Planning Complexities

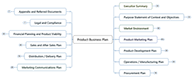

|PMM Business Planning Frameworks

Best practice Product Management as defined, is made up of 3 primary subject areas which in turn are individual disciplines in their own right, entitled: Programme Management, Market Development and Strategic Portfolio Management.

PMM 'frameworks' have been meticulously developed with an open architectural footprint, this enables you manage your Products / Services across individual 'life-cycles' and are structurally generic and robust for use in 'any' business. Obviously there is no such thing as a 'generic business', they come in all shapes and sizes with their own unique quirks and idiosyncrasies. As such this must be to be taken into account when deploying any management processes - it has to be right for the organisation concerned - a management process that is an incorrect fit or goes against the culture will be badly received and soon fall into disrepute. Senior management must believe in the system / process with a passion and results will undoubtedly flow thereafter.

The following defined variations are 'primary' variants (alignments) which have been further described thereafter :

1. Product Manager (Programme Management) + Market Development Alignment

2. Market Development Alignment

3. Product Manager Alignment

4. Entrepreneurial (Start-up) Alignment

1

.jpg)

21

3

4

.jpg)

‘Click to Expand’

| Product Marketing LifeCycle - Market Development Vs Regional / Segment Development

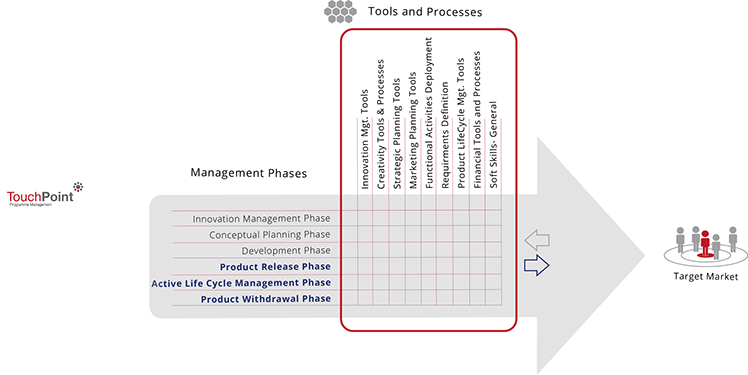

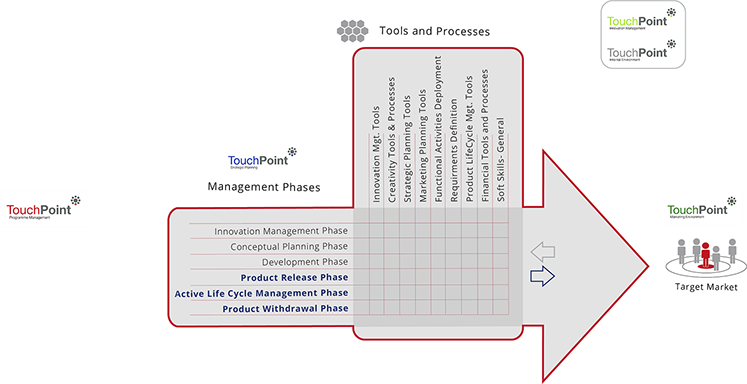

|Management Phase Vs Tools and Processes

743x364.png?crc=4093201072)

|Product Management Generic Tips and Ideas

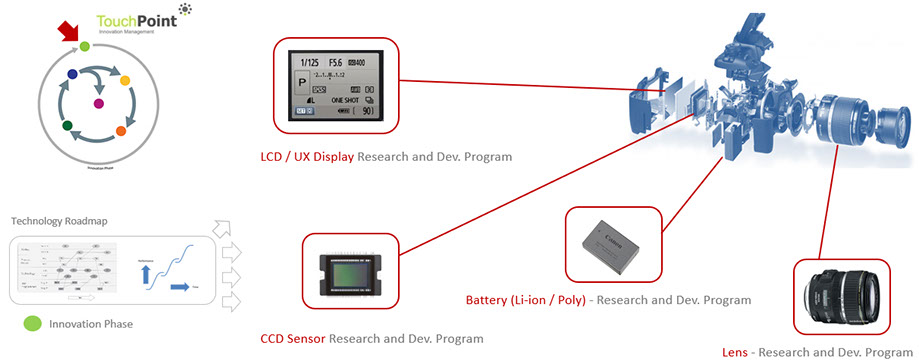

Successful Product Innovation requires more than the ability to create ideas and good design. It requires a competitive organisation.

Success in today’s extremely competitive environment requires excellence and focus throughout the organisation — all areas of activity. Such as strategy, product management, design, manufacturing, sales and service must contribute to the success of a new product. The sum of the parts in terms of capabilities must align to genuine core competencies.

For many disciplines these tips provide advice that will improve the chances of success, based on simple, non-contradictory guidelines. They may prove of some use for a wide spectrum of readers, from young designers to directors and top management.

Reduce Time-scales and Activities wherever possible...

The reduction of time-scales and activities is an essential factor that directly effects dynamics and agility of the Company. In all functional areas of activity, from Research, Development, Operations to Service, there are vast possibilities for improvement.

Measuring is a prerequisite for achieving increased performance. From the moment we start measuring the things we want to improve, we create the awareness that is needed, we make visible what is wrong, can monitor the improvements process.

Simplify Simplify Simplify

Confusing organisational structures, difficult to use products, complicated layouts, over complex logistics, confused reporting, etc. have direct consequences for the resulting cost structure. Every level in the organisation, every step-in distribution, every component in a design, every storage activity, every responsibility shared with others, every processing step in manufacturing, etc. can be translated into terms of people and equipment that are a direct result of that factor.

Co-operate

Teams, meetings, committees, groups, etc. are an inevitable part of daily life in our company. Members represent functionally oriented groups, such as marketing, sales, development, manufacturing, planning, accounting, etc. Most functions show a tendency to suffer from a distortion of perspective that makes their own problems and responsibilities appear much more important than those of other functions.

This can easily lead to ‘tribal’ conflicts and political behaviour, blurring the picture of the real adversary: the competition. The most important goal of the team is to co-operate, and form a new tribe, with one aim:

To be better than and out-perform the competition.

Measure

The measurement of performance is an integral part of improvement activities. Much of our management reporting is done in financial terms, which in most cases is the result of a complicated process, finally translated into money. This gives little or no indication which managers can use as a basis for corrective action.

Processes must be controlled by the process parameters, and not by the financial results. The word ‘result’ expresses exactly what it should be: a result. It becomes an indicator afterwards, showing whether the process was controlled correctly or not. We must choose those process parameters that are vital for the control of the process and use these for day-to-day management.

Innovation = uncertainty

Creating new products and new markets is like exploring new continents. Thanks to creativity, stubbornness and/or vision, we discover new land and territory, with unlimited opportunities and unknown dangers. Nobody can tell us what lies before us; we can only rely on the courage and the professional qualities of our group of explorers, soldiers and traders.

New technologies and new products provide us with many more opportunities than anyone can dream of. We must live with these uncertainties and forge ahead.

When you are ahead of the competition, there is no one you can follow and if you look back too much, you may stumble and fall.

Make your strategy and tactics so clear and simple that you can explain them to every level in your organisation.

When you cannot explain your strategy and tactics in clear and simple terms to your colleagues and to lower levels of the organisation, this may be an indication that you do not understand them clearly yourself.

The danger of an organisation that is not aware of the course to be followed is greater than the danger of leaking information to the competition.

Pick your most dangerous competitors and analyse their strategy and tactics.

Select the companies that represent the most dangerous competition. Collect all available information, not only on their products, but on every possible aspect. Watch them closely and analyse their history, their management structure, their marketing tactics, their cost structure, their manufacturing set-up, their technologies, etc. and try to visualise the underlying strategy. This provides a basis for predicting their course and anticipating on their future actions.

Keep in direct contact with your markets and customers. Every extra link in the information flow adversely affects quality. Market information is like fish: it is only good for consumption when it is fresh.

It is a law of mathematics that when a object increases in size, the volume increases by the third power of the linear dimension, and the outer surface increases only by the second power. Twice the linear size therefore means eight times in volume, and four times in surface area.

When our organisations grow in volume, the self-generated problems within the organisation tend to increase in number and size. As a result there is a strong tendency to spend too much time on internal problems and too little on the outside world. Orientation towards the customer as the most important factor tends to suffer. What is appreciated by the customer is good for the company, and not the other way round.

Define a steady course for your Product Portfolio. Try out new products or experiments as a sideline before changing course.

Change the course of the Product Portfolio gradually. Sudden changes, as in daily traffic, mean increased risks, higher fuel consumption, greater wear on tyres, etc. Step-by-step adjustments should be the basis of the policy, building further on the existing position. New ideas must be evaluated and tried out in parallel with existing processes. In all instances a transformation strategy must be well thought through before a leap into the unknown. Measure and Improve - use the RADAR model (in this PMM framework) to measure strategic impact on any change (for better or worse).

Simplify your product range. This will result in a reduction of overhead costs.

Approximately 50% of a company’'s overhead cost structure in manufacturing is directly connected with diversity. The most effective attack on overhead costs (and not only manufacturing overheads) is therefore based on the reduction of diversity. The ‘productivity’ of the various types in the programme should be monitored closely against fixed targets. ‘Productivity’ may be defined as the ratio between profit and specific initial costs.

Keep a close eye on the percentage of new products in the turnover. New products are the basis of future profitability and vitally important for company longevity.

It is a generally accepted fact that a regular flow of new products or renewed products is a major factor for achieving sustained growth and profitability. A dependable indicator that can help you keep track on the performance of product groups in this respect can be found by measuring the percentage of the total turnover that is accounted for by products that were not on sale two or three years ago. A simple graph updated on a yearly basis speaks for itself. In parallel with this activity you may wish to use the MFP model within the framework to map an entire portfolio.

.jpg?crc=3851828413)

%20mgr%20alignment%203136x115.png?crc=4144507423)